Daybook: On discarded Christmas trees

Every day from 2017 to 2020, I walked a mile and a half to and from work, through the neighborhood where I lived in Berkeley. I love walking, and I particularly love walking to and from work as a way to start and end the day; when we lived in California, we chose our first apartment based in part on proximity to my office. (It has to be the right proximity, i.e., not too close that the walk wouldn’t take at least twenty minutes.)

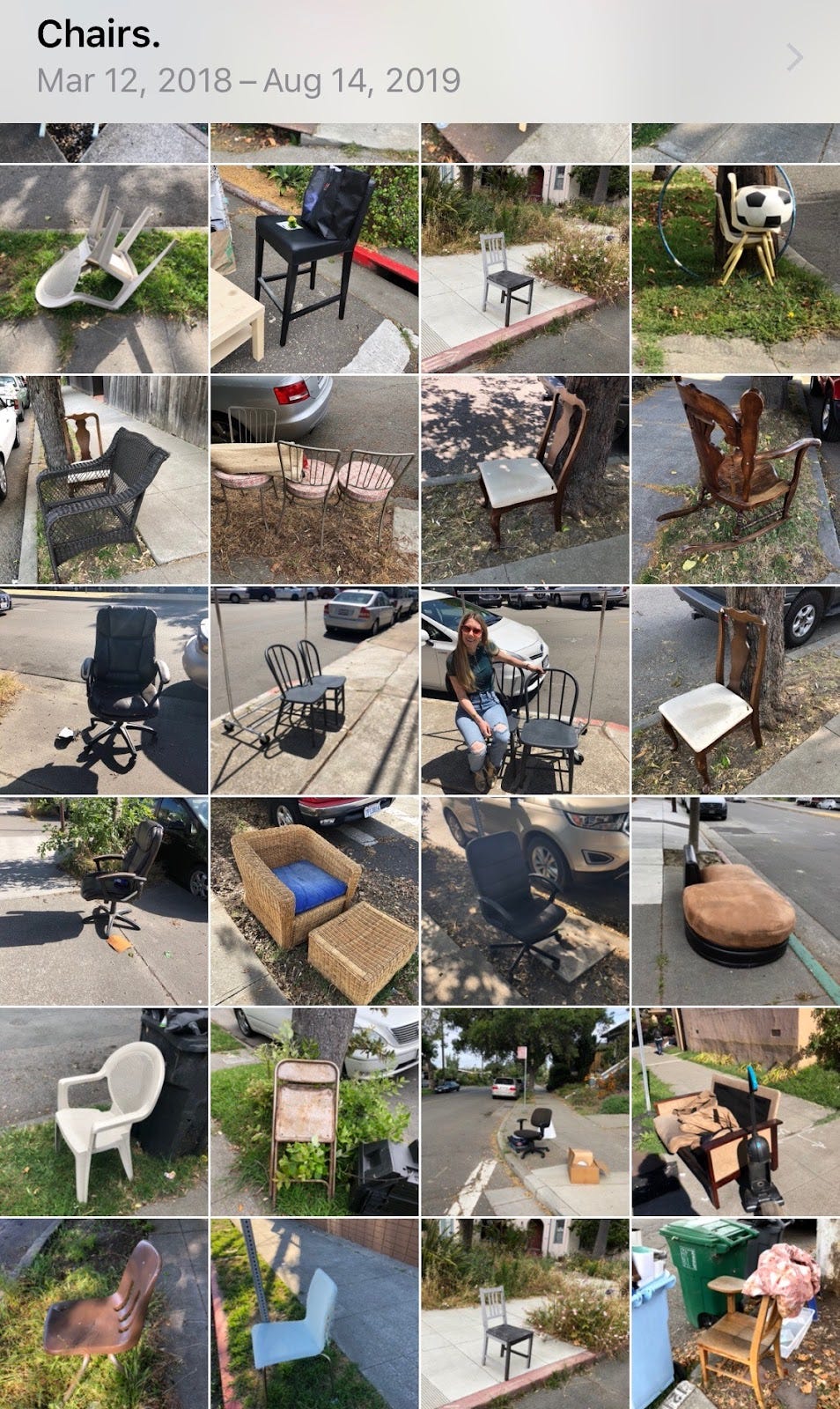

A few months into my walking commute, I began to notice how many things were left out on the curb. Chairs, especially. Sofa chairs, wooden dining room chairs, wrought iron, wicker. All these empty seating arrangements, left like a world left without humans. Once, for about three full weeks, a baby’s high chair haunted the corner of Alton and Russell, in an eerie evocation of Hemingway’s six-word story. At times, this neighborhood habit seemed so uncanny that I absently wondered if it was some sort of slowly unfolding art installation—I’ve held lots of regular walking routes in this lifetime, but nowhere else had I seen so many chairs.

It was easier to notice objects on the curb in the mornings, maybe because my mind hadn’t yet been cluttered by a day’s worth of tasks and email. For two weeks, there was a blue rocking chair parked in front of a house on Sacramento Street, a char I rarely noticed on my way home, only while walking to work, when my eyes were alert and fresh, when I wasn’t mulling over the day’s small slights and aggressions, the unanswered emails, the blown-to-the-wind to-do lists. The chairs made me realize that I spent most of my afternoon walks on autopilot, still mentally parked in my office as my body unthinkingly walks itself home. If I wasn’t careful, my surroundings took on a quality so secondary to myself that they almost didn’t exist. It was almost as if reality became virtual reality. That unsettled me.

I began to take pictures of the chairs. Partly to keep myself rooted in my environment, and partly because I wanted to draw them. Sprawled on the side of the sidewalk like that, they seemed like margin notes—a sort of commentary not on a text, but on the way we live: how easily we discard, and how we expect some other faceless, unknown entity to make our unwanted objects and waste vanish. (While first writing this, I was also reading Brenda Shaugnessy’s 2019 collection of poems about the end of the world, The Octopus Museum, in which she writes: “You’ll miss the luxurious wastefulness and the way our waste became invisible to us. Wasting everything was what kept us warm, sleeping cozily, so clean all the time.”) Maybe, I thought, by painting or drawing the chairs, I could somehow employ them again.

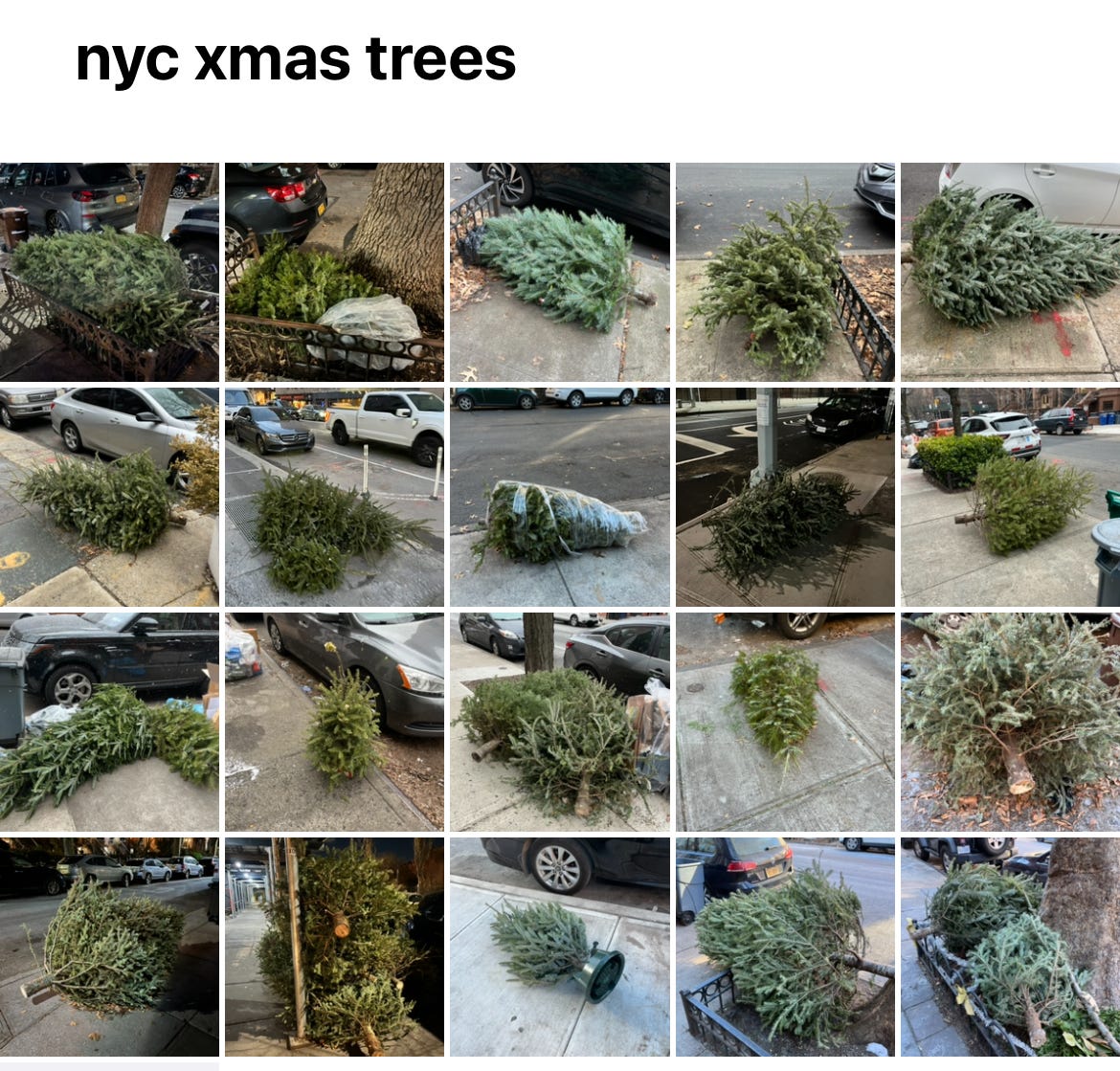

So I was already in the habit of taking these photos when the beginning of my first January in Berkeley rolled around, and Christmas trees garnished the curbs instead. There were so many on my first walk to work after the holiday break that it was almost comical, all these dead lopsided evergreens which we hunted, decorated, and endowed with value for one to three weeks, and then suddenly were desperate to get rid off. A tree is not a chair. They were once—more blatantly, at least—alive. They made me feel like an alien. And then they made me laugh.

That first morning, I took a photo of each tree and posted them to my Instagram story.

A few days later, on my walk home, my mind stuck in email vernacular after a day at work, I started posting images of Christmas trees with email sign-off language as captions.

Not all of the photos I posted used this language, but they were my favorites, for how they encapsulated the dried-out husk I feel I am as I prepare to press send on my fortieth email of the morning, using stock phrases (“I hope this finds you well!” “Happy Friday!”) that don’t signify my character, but that, for all intents and purposes, is me to the other person opening the email on the other side of the country. As I type “All best” or “Thanks for your time,” or “Warmly,” I become literally anyone and everyone else. My original intentions—to simply be polite to strangers—scramble into code. I feel my actual self fall away and land on the curb, a corpse of needles and branches.

Dramatic!! But I liked how the absurdity of our work email vocabulary illustrated the beautiful absurdity of keeping decorated trees in our homes for a couple weeks every December. I liked the inanity of imagining trees signing off after their long workday of giving us a magical holiday season. (Perhaps I should mention that my day job is in book publicity, where I’m ideally supposed to give every book, upon publication, its own magical holiday season.)

What once was a pagan solstice ritual to bring light and nature indoors during the darkness and desolation of winter has now devolved into an annual, automatic impulse to hit up the parking lot of Lowe’s once the calendar flips to December. Most of us have long passed the point of being so connected with nature, of actually thinking about what we’re doing. We’re on autopilot. I can’t tell you what kind of evergreen tree we had in our living room this past Christmas, or the year before that. Was it a blue spruce, a Scotch pine? No idea. Until I started taking pictures of the chairs and the Christmas trees, I had not really before considered how easy it can be to water down the world so that it exists only where our bodies are. To believe that our houses, the holding place of our material belongings, are our only home, instead of seeing them as part of a larger ecosystem.

(This past year in New York, Brad and I walked down to the bodega on the corner to get our Christmas tree and when we asked how much it was, the tree guy said it would be $120. Panic gripped me. How was that possible? Yet I had to have it. I wanted a tree inside of my small apartment! I wanted to smell it when I woke up in the mornings! Where do those desires come from? Where did these trees come from? Who cut the trees down and who got them to this bodega? What makes them 120 dollars? What is the value of a tree?1)

In the winters that followed, when the trees reappeared and I began posting pictures of them again, my friends sent me their own photos of discarded trees, sometimes with their own captions—like a collaborative art project. I had unintentionally created a morbid way to be in touch with an extended network of friends and friends of friends. I received photos of dumped trees all over the country and from as far as the UK and Italy.

The trees acted as short but often shocking interruptions in my regular day, as I came across one stuffed in a trash can, or sprawled across the sidewalk, or leaned against a planted, still alive oak tree. I identified with them; they spoke to some debased part of myself—tired of trying so hard to be “successful” at my job, my writing, in my friendships, my relationship, my body; tired of pretending to live each day as normal when the very idea of normalcy seemed more and more absurd (in the face of apocalyptic yet underestimated climate reports, and then also during a pandemic, and now also during the genocide in Gaza). To even have ambition seems ridiculous, and success, in such a context, is mostly meaningless. The evergreens spoke to an exhausted, and yes, very selfish, part of me that just wanted to lay down on the curb, waiting for the trash collector to take me away. RIP ME. But this emotional mirroring also gave me delight. The trees offered an opportunity to poke fun at my personal anxieties, which were overwhelmingly trivial in comparison to worldwide suffering. (And also trivial in comparison to what might be anxiety-inducing for a tree, or nature at large.)

I feel a little weird about making trees a stand-in for my feelings under late capitalism—they truly do not deserve it—but maybe it’s not just a metaphor. In her book The Second Body, Daisy Hildyard writes of how every human has two bodies. The first is our physical, individual body, which we occupy and perceive only on the small scale of the everyday: driving to work, making dinner at the kitchen counter, rolling the trash to the curb. The second body is the global consequences of that seemingly individual body: the dinner it cooks, the trash it discards. “If your second body is determined by its consumptions and emissions,” she writes, “then there is no meaningful difference between your body and a cow or even a car.” Or a Douglas fir.

Is it totally out of the realm of reason to wonder if trees feel a sense of desperation too?

In the winter of 2019, I attended a talk by Ross Simonini and Leslie Shows at KADIST in San Francisco. The talk was called “The Feeling Sense,” a term coined by herbalist Stephen Harrod Buhner, author of Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, to mean “the perceptual capacity of any living organism to encounter their environment.” Buhner argued that plants are intelligent creatures, like us, who are also able to communicate. We just don’t perceive this communication because they exist and act within a separate “time space” as us.

To illustrate this, Shows and Simonini presented a sped-up video of a plant growing toward a vertical rod. At first, it can’t quite reach the rod in order to wrap itself around it and gain stability, so it cranes back to get momentum and launches itself, over and over again, at the rod—an astonishingly human movement, the way one might strain and stretch to reach a glass inside the highest cabinet in the kitchen—before it finally attaches. The plant displayed the same sort of effort that exhausts and overwhelms me, and yet it was resilient. Maybe even more resilient than I could ever be. It was a strange sensation—once the plant existed in the same “time space” as me, I could see inside it the human. Or perhaps I should look at myself and see inside me the plant.

For a while, I was hopeful that the pandemic would wake us up to the ways that we are all inextricable from the environment and from one another. I think of Eula Biss’s On Immunity, one of the first books that made me realize I’m not just myself, and the similarities it shares with Daisy Hildyard’s The Second Body. When it comes to vaccines, “we are protected not so much by our own skin, but by what is beyond it. The boundaries between our bodies begin to dissolve here,” Biss writes, explaining how a vaccinated person living in a mostly unvaccinated community is more at-risk than an unvaccinated person in a largely vaccinated community. I remember watching a movie in my living room in March 2020, right before everything shut down, realizing I was sitting not just next to my husband, but everyone he saw that day. Biss urges us to “imagine the action of a vaccine not just in terms of how it affects a single body, but also in terms of how it affects the collective body of a community.”

Shortly after seeing that talk at KADIST, Brad and I went on a hike in Point Reyes, the first leg of which climbed for three miles through a thick forest of tall, skinny pine trees. Everywhere we were surrounded by the vertical brown lines of trunks, as if we were hiking through a dense crosshatched etching. For one stretch along a ridge, I could sense an expanse just beyond the trees—a drop into the ocean, or a clearing into a meadow. Birds flew behind the trunks and seemed to vanish, their birdsong suddenly deleted, as if they had crossed over into a different world. It was then, confronted with some hidden enormity, that my sense of proportions suddenly shifted. The forest grew even larger, and I even smaller, and I saw with clarity that the trees all around me were not decorative, static objects but alive and growing, looking right back at me. I was in their home. I felt two things at once: first, that I was an invader, and second, that, compared to those trees, I did not matter—how could I, in a forest that’s been around for thousands of years?

Unfortunately, the opposite, of course, is also true: I matter way too much; or rather, all humans do. We matter not in our individualities but in the sense of our collective damage. The accumulation of our lifestyles and political structures threaten the very environment that gives us our lives. Researching interviews with Stephen Herrod Buhner, I came across an essay by Alice Walker called “Everything is a Human Being,” that illustrates this. She writes about going to a park with a friend to lie down beneath a grove of trees, where she begins an “intense dialogue” with them. After awhile, she understands that the trees are telling her to leave:

“As I was lying there, really across their feet, I felt or ‘heard’ with my feelings the distinct request from them that I remove myself. . . . It was then that I looked up and around me into the ‘faces.’ These ‘faces’ were all middle-aged to old conifers, and they were all suffering from some kind of disease. . . . I saw that the ground from which they emerged was gray and dead-looking, as if it had been poisoned. Aha, I thought, this is obviously a place where chemicals were dumped. The soil has been poisoned, the trees afflicted, slowly dying, and they do not like it. I hastily communicated this deduction to the trees and asked that they understand it was not I who had done this. . . . But they were not appeased. Get up. Go away, they replied. But I refused to move. Nor could I. I needed to make them agree to my innocence.”

I love that in that last sentence, Walker implicates herself: she doesn’t try to argue that she is innocent, she just wants the trees to agree that she is innocent. She wants, like so many of us, to escape culpability.

Walker pleads with them, tries to make them understand that it was not her causing them pain, but lumber companies. (“I love trees, I said. Human, please, they replied.”) She would never personally slash and burn and cut down forests, she tells them, though in the back of her mind she realizes she lives in a wood house, with wood furniture; that she has benefited from the slashing and burning. But:

“Finally . . . I understood what the trees were telling me: Being an individual doesn’t matter. Just as human beings perceive all trees as one (didn’t a U.S. official say recently that ‘when you’ve seen one tree, you’ve seen ‘em all’?), all human beings, to the trees, are one. We are judged by our worst collective behavior, since it is so vast; not by our singular best.”

It’s difficult for me to wrap my mind around the contradiction inherent in this particular iteration of “being an individual doesn’t matter,” with its implication that the opposite is also true. The individual does matter, especially if it does nothing to combat the collective—is actually no different than the collective. It’s almost like the individual doesn’t exist at all.

The sense of insignificance I experienced in that forest in Point Reyes runs adjacent to the relief that washes over me when I’m in the presence of very large, naturally-occurring landforms: mountains, for example, or towering redwoods. I have the overwhelming realization that all this will still continue—indeed, will have a better chance at continuing—long after I’m gone. The earth doesn’t need me in order to be the earth. It feels good and peaceful to acknowledge this, to relinquish any sense of importance, to drag my selfhood out to the curb.

Is this just another way of absolving myself of responsibility, though? Maybe the reason it feels good and peaceful is because it fools me into believing my own innocence. In her book Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino writes about wandering through the desert on drugs: “I wanted to see the landscape as it was when I wasn’t there,” she says, referencing Simone Weil’s fantasy of disappearance. I’m not sure if this version of looking is the same thing as looking away, feigning non complicity; or if it’s a radical expansion of what’s possible—to imagine a landscape as unmarred as possible by human damage, as a way of building a foundation toward achieving just that. The earth might not need me in order to be the earth, but we need the earth, and and we need each other. What would the landscape look like if we could co-exist with it peacefully instead of dominating it wholly?

I’m not so interested in the Christmas trees anymore. I still take photos of them but I don’t post them as often because I don’t know what to say. Part of it is that, by writing this, I’ve now explained my interest in them to myself, and therefore, killed the fun. The other part is that continuing the joke year after year feels equally deadening as going through the motions while every day the world is eaten up and burned by our greed. I want to stop going through the motions, fall to the ground. Not to await being dragged away, but because an interruption of daily life “as normal” feels like what is most required.

Reading: On Not Being Able to Paint, by Marion Milner. Solenoid, by Mircea Cărtărescu. Fog and Smoke by Katie Peterson. East of Eden by John Steinbeck.

In light of the LA fires: “In LA” by Colm Tóibín and “California Burns” by Mike Davis, both in the London Review of Books. “Escaping Los Angeles” by Kerry Howley in New York Magazine.

Donate to the Anti-Recidivism Coalition (type “firefighter fund” in the payment box) to support the incarcerated fire crews who are currently fighting the Los Angeles wildfires.

“Where to donate to people who’ve lost their homes in the LA fires,” a list compiled by Rachel Davies.

Of course, these are the kind of questions that usually have answers (even if I find the fact that a tree carries monetary value existentially unsavory). While putting this newsletter together I stumbled upon Devin Kelly’s 2018 essay for The Outline, “A day with the Christmas tree vendors of New York,” which delves into some of these logistics—and is also a really interesting piece on the community of tree vendors in general! (Coincidentally Devin also writes a newsletter about poetry called “Ordinary Plots” which I really enjoy and highly recommend.)

omg i really did restrain myself from sending you all the christmas trees on my block this year bc i was like, she's probably over it/it would be annoying